‘Black Loyalists at Birchtown’ Plaque

Birchtown, Nova Scotia

The National Historic Event of Canada plaque located in the Black Loyalist Heritage Park in Birchtown, Nova Scotia commemorates Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

The inscription of one plaque unveiled in July 1996 reads as follows:

THE BLACK LOYALISTS AT BIRCHTOWN

LES LOYALISTES NOIRS à BIRCHTOWNAfter the American Revolution, over 3500 free African Americans loyal to the Crown moved to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick where they established the first Black communities in Canada. Birchtown, founded in 1783 was the largest and most influential of these settlements. The population declined in 1792 when many Black Loyalists, frustrated by their treatment in the Maritimes, emigrated to Sierra Leone in West Africa. Although diminished in numbers, Birchtown remains a proud symbol of the struggle by Blacks in the Maritimes and elsewhere for justice and dignity.

Après la révolution américaine, plus de 3 500 Afro-Americains libres, loyaux à la Couronne, immigrèrent en Nouvelle-écosse et au Nouveau-Brunswick, où ils établirent les premiéres communantés noires au Canada. Birchtown, fondée en 1783, était la plus grande et la plus influente de celles-ci. Sa population déclina en 1792, lorsque de nombreaux loyalistes noirs, dépités du traitement reçu dans les Maritimes, émigrèrent en Sierra Leone (Afrique de l’Ouest). Birchtown demeure néanmoins un symbole glorieux de la lutte pour la justice et la dignité menée par les Noirs des Maritimes et d’ailleurs.

Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada

Commission des lieux et monuments historiques du Canada

Government of Canada – Gouvernement du Canada1996

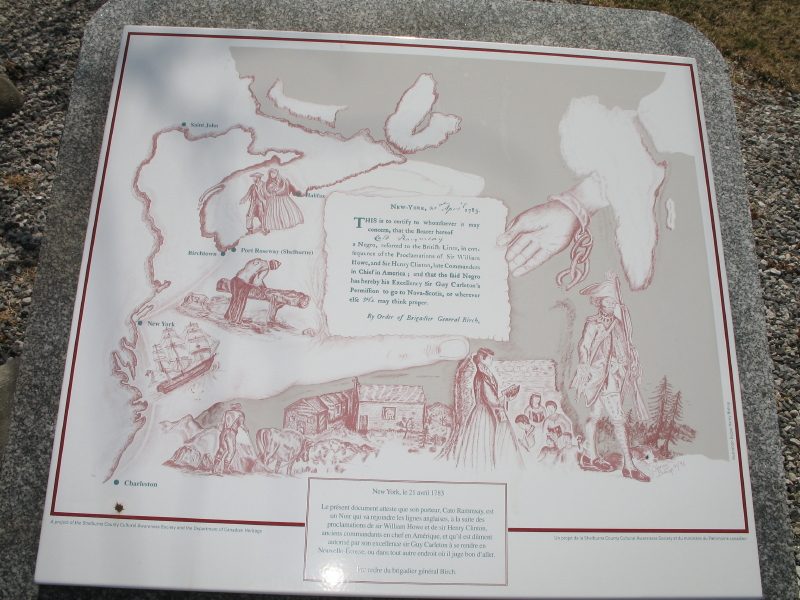

The second marker includes a map and illustration of a permit granted for passage from New York:

The two markers:

(Photography by Betty Camp)

The Historic Significance of Birchtown

By Daurene E. Lewis

Extracted from the Shelburne Coast Guard newspaper and printed in the Loyalist Gazette, Vol. XXXIV No. 2 Fall 1996 pages 37/38

Note: Following is the complete text of the address by former Annapolis Mayor Daurene Lewis on the “Historic Significance of Birchtown” presented on Saturday July 20 during unveiling ceremonies for two plaques recognizing the national historic significance of the settlement by Black Loyalists at Birchtown in 1783.

The African presence in North America was not expected to be permanent. The life expectancy of a slave was anticipated to be seven years. The projection was that every seven years the labour force would have to be replaced. We were not viewed as human being, but rather instruments in the labour process. Our story started with the most dramatic forced migration in history, which saw 15,000,000 of us brought from Africa in bondage to the Western Hemisphere. We were dumped into a cauldron of unfamiliar cultures, unfamiliar language, unfamiliar religions and an unwelcoming land. Our tribal groupings were destroyed, our families separated, but against all odds we survived. Many of us survived to reach Nova Scotia.

There were three main sources of black settlers in ova Scotia: 1)”servants for life”; 2) black pioneers; 3) black Loyalists.

“Servants for life” was a euphemism for slaves since slavery was not officially condoned because the removal of slaves from their owners in the U.S., violated the American provisional articles. Many of these “servants” were offered freedom after the death of their master and came to Nova Scotia with the United Empire Loyalists. Others were still being referred to as servants even when they were sold.

The second group of settlers was the black pioneers. They were labourers who followed the army and provided maintenance functions. They were paid for their work, but were not fighting men. The third group of settlers was the black Loyalists. They were recruited by the British as early as 1775 to serve in the army and navy. There were two main reasons for the recruitment: 1) to deplete the American (rebel) workforce, and 2) for the British to gain a workforce for themselves. Both men and women were welcomed by the British to serve in the military. The women cooked, did the laundry and sewing or served as nurses. The men served as teamsters, and they were armed and fought alongside of the British troops

Sir Guy Carleton, Commander-in-Chief of the British troops in North America, guaranteed their freedom if they joined the military to fight against the Americans in the war of independence.

In nearly every location in Nova Scotia, the black settlers were segregated frequently in unyielding sites. In Annapolis County, 76 free blacks received land grants in 1785; all were for a single acre. This compared to grants of 50 to 200 acres for white settlers.

It was expected that Shelburne would be a model community for the resettlement of blacks in Nova Scotia. The ‘servants’ in Shelburne continued to live with their masters, but most blacks lived in a community of their own called Birchtown./ By 1787 there were approximately 200 families in Birchtown and another 70- families in the northern division of the township. In july 1784, the muster roll shoed a total of 5,900 whites and 2,700 blacks. Of these, 1521 blacks were free.

They came with a variety of skills—carpenters, rope makers, boat builders, sawyers, chimney sweeps, seamstresses and sailors. Therefore, our labour was useful to the white inhabitants in helping Shelburne become the most prosperous community in the province in those early days.

Harmony between the whites in Shelburne and the blacks in Birchtown did not last. In July 1784, to quote Simeon Perkins, ” an extraordinary mob: comprised of hundreds of disbanded white sildiers rampaged through the settlement of Birchtown and destroyed many homes.

Relations between the whites of Shelburne and the blacks of Birchtown were never the same.

By 1789 the town fathers of Shelburne passed an ordinance warning blacks against holding dances and frolics in the town of Shelburne. The exodus of free blacks to Sierra Leone in 1792 accentuated and accelerated the decline of the community of Birchtown. The optimism and success of the early days were lost. The glory days passed and the harsh reality of new struggles began. Here we stand more than 200 years later to applaud and celebrate the brief but glorious success of the community of Birchtown.

A tribute to our quest for freedom.

A pillar of our heritage.

A beacon for our future